A recurring theme in my research is to analyze the observed orbital architectures of planets, moons or orbital debris to help characterize those systems and learn about their history and possible formation scenarios. In collaboration with Hanno Rein, I have also put a lot of time into developing open-source numerical tools for such work that have been widely adopted by the community.

I apply these techniques in our own solar system with the Cassini spacecraft around Saturn, as well as on the rapidly growing sample of planets discovered around other stars.

Undergraduate or first-year graduate authors (with similar course loads) are marked with asterisks (*), and more senior graduate students with carets (^).The TRAPPIST-1 system consists of seven Earth-sized planets that are prime candidates in the search for alien life. The system's proximity to us means that starting next year, the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will be able to look for important biosignatures in their atmospheres.

One puzzle was that when the discovery team simulated the system, the planets crashed into one another on extremely short timescales. But direct observations do not strongly constrain important parameters like the eccentricities and orientations of the orbits. By simulating the formation of the TRAPPIST-1 system, we showed that interactions with the surrounding birth disk can allow the planets to tune themselves into a stable configuration that is stable over many billions of orbits.

A remarkable orbital feature is that the TRAPPIST-1 planets are in the longest known resonant chain, a clockwork configuration of precisely tuned orbital period ratios. We translated these rhythmic motions into music, with surprising results. Check out the video, coverage of our research in the New York Times, and radio interviews on Canadian and Spanish radio.

Observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array revealed these spectacular set of concentric gaps in the circumstellar disk surrounding the young star HL Tau. This may be the first time we see giant planets in formation as they carve out the material along their orbits.

But there is a tension here. The gaps are very close to one another. The planets need to be massive enough to carve out the gaps, but they can't be too massive or they would gravitationally scatter off one another, destroying the observed concentric structure. Through numerical integrations, we find that planets are indeed a viable explanation. You can find a longer writeup on this page.

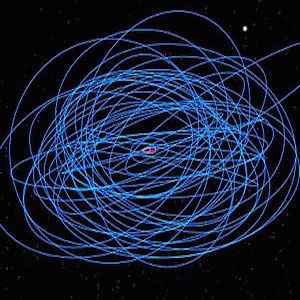

Fomalhaut b is almost as controversial as it is famous, as the first directly imaged planetary candidate. The fact that infrared surveys have not been able to detect it suggests that what's seen in these and previous images from the Hubble space telescope (at optical wavelengths) may be reflected light from a collisional swarm of irregular satellites.

However, follow-up Hubble observations reveal that, surprisingly, the object moves on an extremely eccentric orbit. We showed that this would have dramatic effects on the observed circumstellar debris disk (the big ellipse prominent in the picture). The fact that we instead observe the debris disk to be sharp and confined allowed us to set stringent limits on the putative planet's mass and on the time it can have been on its present orbit.

An interesting implication is that if Fomalhaut b is indeed a giant planet (and is the only planet in the system), then we are catching the disk on its way to becoming extremely eccentric in the next few Myr. This will bring all the material into the inner Fomalhaut system, roughly analogous to the hypothesized Late Heavy Bombardment in our Solar System.

The irregular satellites are leftovers from the era of planet formation that were captured around each of our solar system's giant planets. As a result of this chaotic capture process, they form a swarm of mutually crossing orbits, and have been crashing violently into each other for the past 4.5 billion years. I am working with the Cassini spacecraft to detect and characterize the resultant disk of debris around Saturn (the Phoebe ring) in order to learn more about these ancient bodies, and to develop a better theoretical understanding of where the material ends up in order to help constrain the Saturnian system's history.

The striking albedo difference between Iapetus' two hemispheres has been a mystery since Giovanni Cassini discovered the moon orbiting Saturn in 1671. It was suggested long ago (Soter 1974) that dark dust from the outer satellites evolving inward through radiation forces might explain Iapetus' odd surface pattern, but we performed the first full analysis calculating the probability of impact with Iapetus and the expected surface distribution.

We found that almost all particle sizes will strike Iapetus, and that the expected longitudinal distribution matches well the one observed, helping settle (at least theoretically!) a 300 year-old mystery.

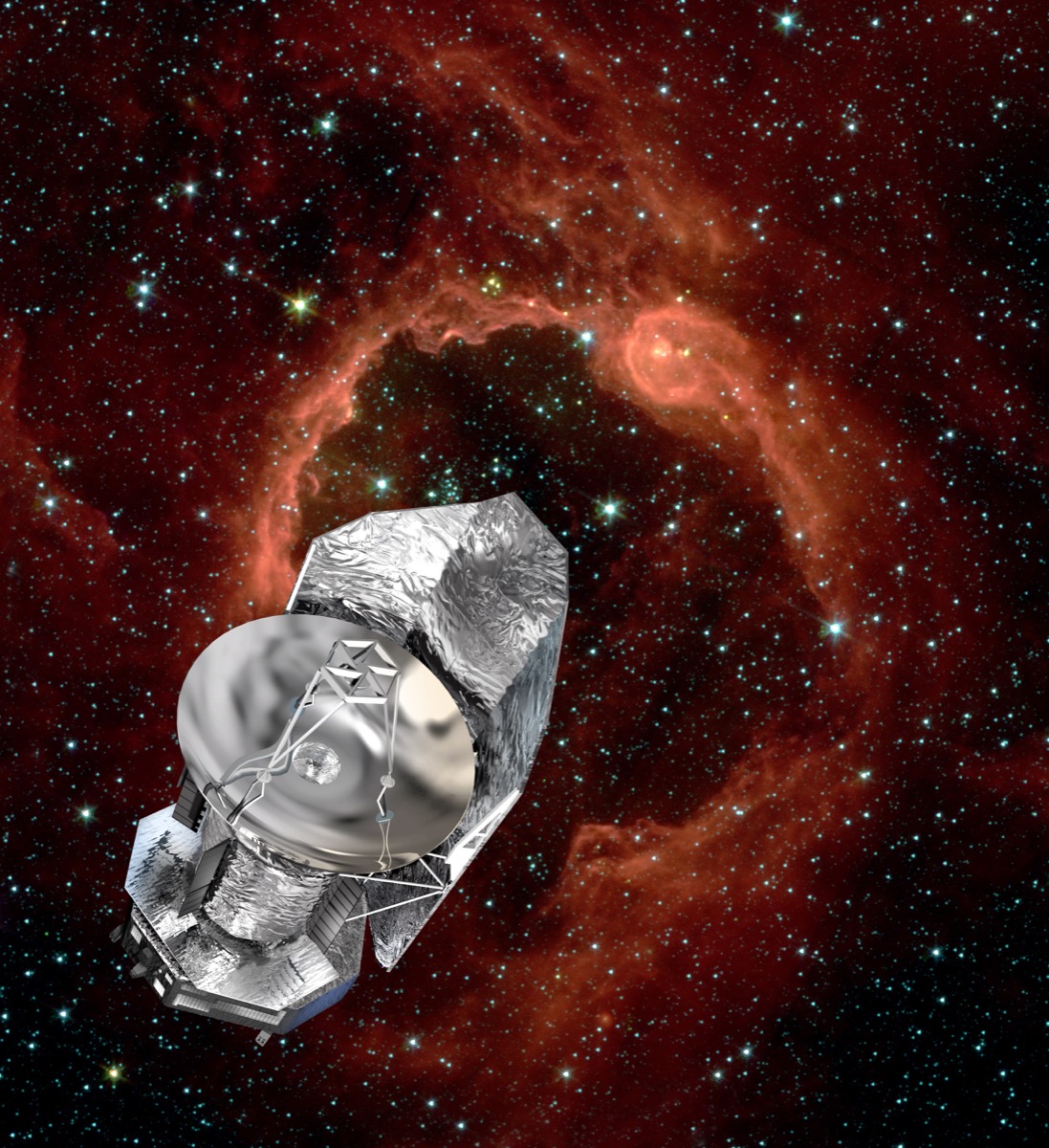

I was the science principal investigator on OT1 and OT2 observations with the infrared Herschel Space Observatory, trying to characterize the Phoebe ring around Saturn, and trying to discover similar debris disks sourced by irregular satellites around Uranus and Neptune. Unfortunately, we were only able to set upper limits on the amount of material present due to scattered light from the respective planets.

One would think that it would be easy to detect the Phoebe ring at Saturn using the Cassini spacecraft in orbit about the planet. The problem is that the ring is so vast, and the spacecraft so close, that the ring covers the entire field of view and provides a constant background that's extremely difficult to separate out.

We therefore came up with a novel observation strategy, and planned for orbital alignments that would allow us to take images capturing Saturn's shadow piercing the Phoebe ring. This made it possible to indirectly measure the amount of material along the shadow by quantifying the brightness difference between the shadowed and unshadowed regions.

Comparing optical to infrared data allowed us to constrain the debris' physical properties, observationally linking it to the irregular satellites. We also measured how the amount of debris varies with distance from Saturn for the first time. I am quite proud of these results--they represent the faintest measurements of any extended solar system object by an order of magnitude!

In trying to undertake a similar analysis to our work on the Saturnian system, we were surprised to find in our integrations that as dust-particle orbits decay inward in the Uranian system, they reach a chaotic zone in which their orbits evolve onto nearly radial paths that bring the debris deep into the inner system.

It turns out this instability is the result of Uranus' extreme axial tilt and the interaction of the planet's oblateness with gravitational perturbations from the Sun. We showed this should spread debris across Uranus' four largest satellites, plausibly explaining hemispherical color dichotomies observed on their surfaces with the Voyager spacecraft.

Determining whether a given planetary system will be dynamically stable over long times, and predicting the timescale on which unstable systems will unravel is an important and long-standing problem in orbital dynamics.

We took the novel approach of numerically integrating a number of planetary systems and using them as examples to train machine learning algorithms that have enjoyed wide success across a range of similarly high-dimensional applications in industry. With these tools we were able to determine whether planetary systems would be stable over 10 million orbits significantly better than simple heuristic criteria previously used in the field, and 1000 times faster than through direct numerical integration.

For a large class of orbital fitting problems, we are interested in how a body's position and/or trajectory would change if our initial parameters for the orbit were slightly wrong (e.g., will a newly discovered asteroid hit Earth!) People therefore derived first-order variational equations to integrate how these differences evolve with time. You can then calculate derivatives with respect to initial parameters that tell you which direction in phase space you needs to move to improve your fit.

We have derived and implemented second-order variational equations, which yield the additional information needed to know how far you need to move to reach the nearest best solution (local minimum). We hope to exploit these tools to build improved orbit-fitting algorithms.

The so-called Wisdom-Holman algorithm revolutionized our ability to carry out planetary orbit integrations accurately and efficiently enough to reach timescales comparable to the age of the solar system. However, previously available implementations were biased, i.e., numerical errors grew coherently, leading to a steep error growth with time.

We have developed WHFast, an unbiased integrator whose numerical error is suppressed to the fundamental limit, while still outperforming the speed of currently available implementations. This is helping us (and others!) push numerical integrations further than ever before.